Search for articles, topics or more

browse by topics

Search for articles, topics or more

What happens to an object at the end of its lifespan? As awareness around the design industry’s impact on the environment has grown in recent years, one of the central challenges is to develop strategies that can cope with the waste generated by products reaching the end of their life cycles. In the words of architect William McDonough, who co-authored the influential 2002 book Cradle to Cradle, “Nature doesn’t have a design problem. People do.”

According to a 2019 report by the World Bank, cities across the globe currently produce more than two billion tonnes of solid waste each year. It is a shocking statistic, and one that suggests all industries need to urgently rethink their approach towards design in order to cut off this waste stream. As part of this drive, numerous strategies have emerged that attempt to address this problem – from working with more environmentally friendly materials and processes, through to close management of supply and distribution chains to ensure maximum efficiency.

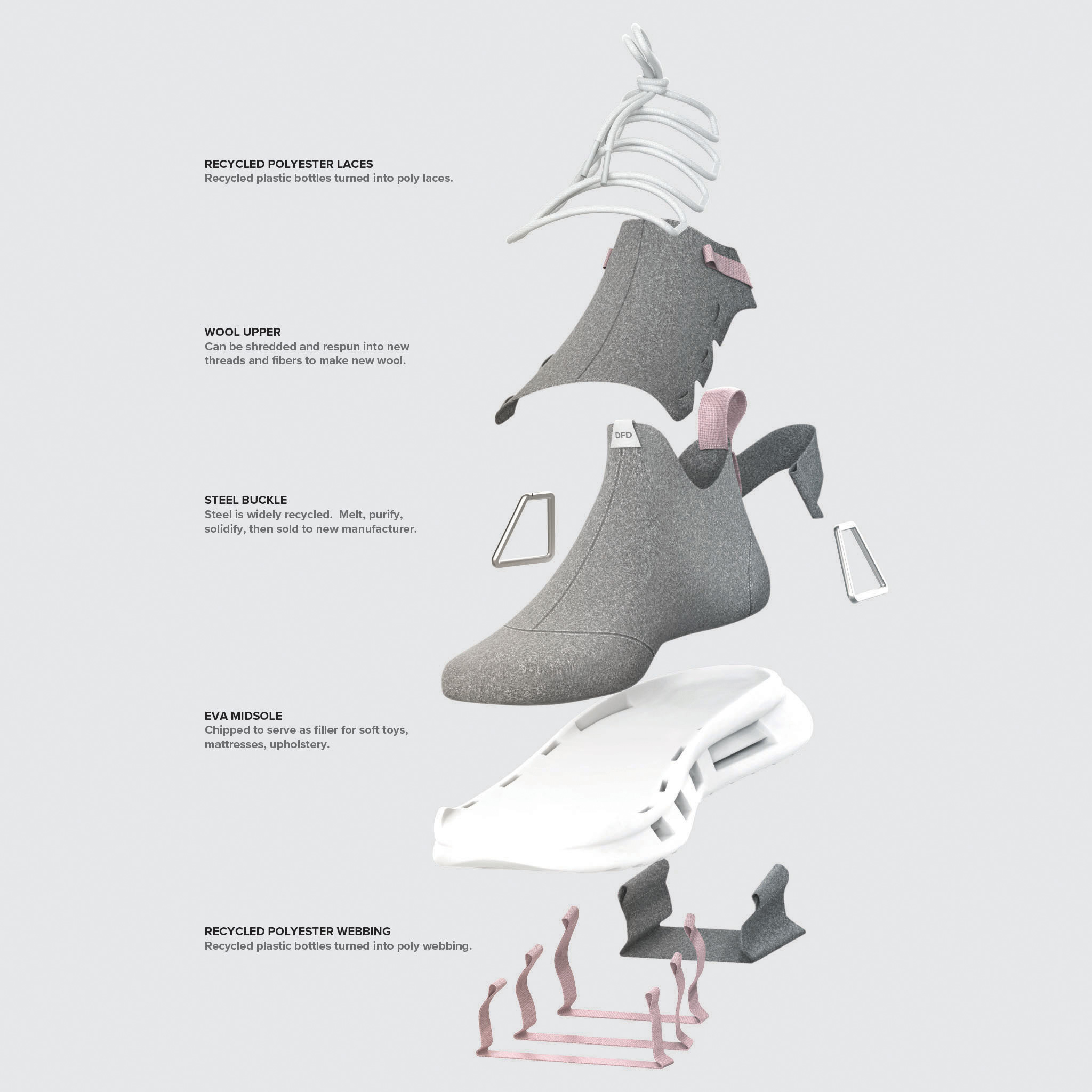

DFD shoe design (2019), Gannon McHugh

DFD shoe design (2019), Gannon McHugh

One of the most promising avenues of inquiry, however, is the rise of design for disassembly: a process by which products are designed with the end of their lifespan as an essential part of the initial brief. Under design for disassembly, any product should be capable of being easily broken down into its constituent materials at the end of its useful life cycle, thereby enabling it to enter existing recycling streams.

This approach is central to Molteni&C’s own sustainability policy. All of the brand’s furniture is designed using mono-materials, and the pieces can be easily dismantled in order to be recovered and recycled. In this sense, the brand is one of a number of industry leaders that are now focusing on the second life of a product. This not only ensures that an object’s environmental footprint can be kept to a minimum, but also pushes designers to think outside the box, resulting in more relevant, creative and future-proof outcomes

The individual components of the DFD design

The individual components of the DFD design

The introduction of Apple’s Daisy robot in 2018, for instance, shone a fresh light on the need for disassembly. This complex robot can take apart up to 200 iPhones per hour, ensuring that each component of the devices can be salvaged and recycled for future use. Apple’s robot has started a conversation within the technology sector about the need to reduce its reliance on mining virgin minerals and encourage circularity. Through Daisy’s process of disassembly, core elements such as lithium can be recovered from an iPhone and then reused elsewhere. Apple is now looking to increase the quantity of recycled ingredients used within its designs and, as stated in its 2019 Environmental Responsibility Report, Daisy is currently able to disassemble 15 different iPhone models. The report also explains that Apple recycled more than 48,000 metric tonnes of e-waste in 2018, incorporating cobalt, tin, aluminium and plastic back into its new designs.

Under design for disassembly, any product should be capable of being easily broken down into its constituent materials at the end of its useful life cycle.

Natural Bond exhibition at Stockholm Furniture and Light Fair (2020), Tarkett and Note Design Studio

Natural Bond exhibition at Stockholm Furniture and Light Fair (2020), Tarkett and Note Design Studio

Designing to limit waste within production, as Apple has done, has given many hope that a circular economy – in which waste becomes the raw material from which future products are made – may be within our grasp. In the fashion world, which has come under a lot of scrutiny for its environmental impact, many labels are now looking to apply a similar mentality. Nike, however, has been moving in this direction for nearly three decades. The American brand’s Reuse-A-Shoe initiative began in 1993, taking used trainers, recycling them and combining them with manufacturing waste into a rubber material dubbed “Nike Grind”.

This material can be repurposed in a variety of applications, with one of the scheme’s first outputs in the 1990s being a series of artificial sports surfaces that incorporated the recycled rubber. Nike Grind has since become an integral ingredient for the brand, recycling more than 32 million pairs of shoes and 54.4 million kilograms of production waste along the way. The company’s latest collection, Space Hippie, makes heavy use of recycled materials and is claimed to be Nike’s lowest carbon footprint shoe to date. Part of Nike’s mission to be a zero carbon and zero waste operation, Space Hippie is created using recycled scrap materials paired with a sole that combines Nike Grind rubber with recycled foam constituents.

“Sustainability has become a core focus and I believe the future generation of designers coming forward will continue this.”

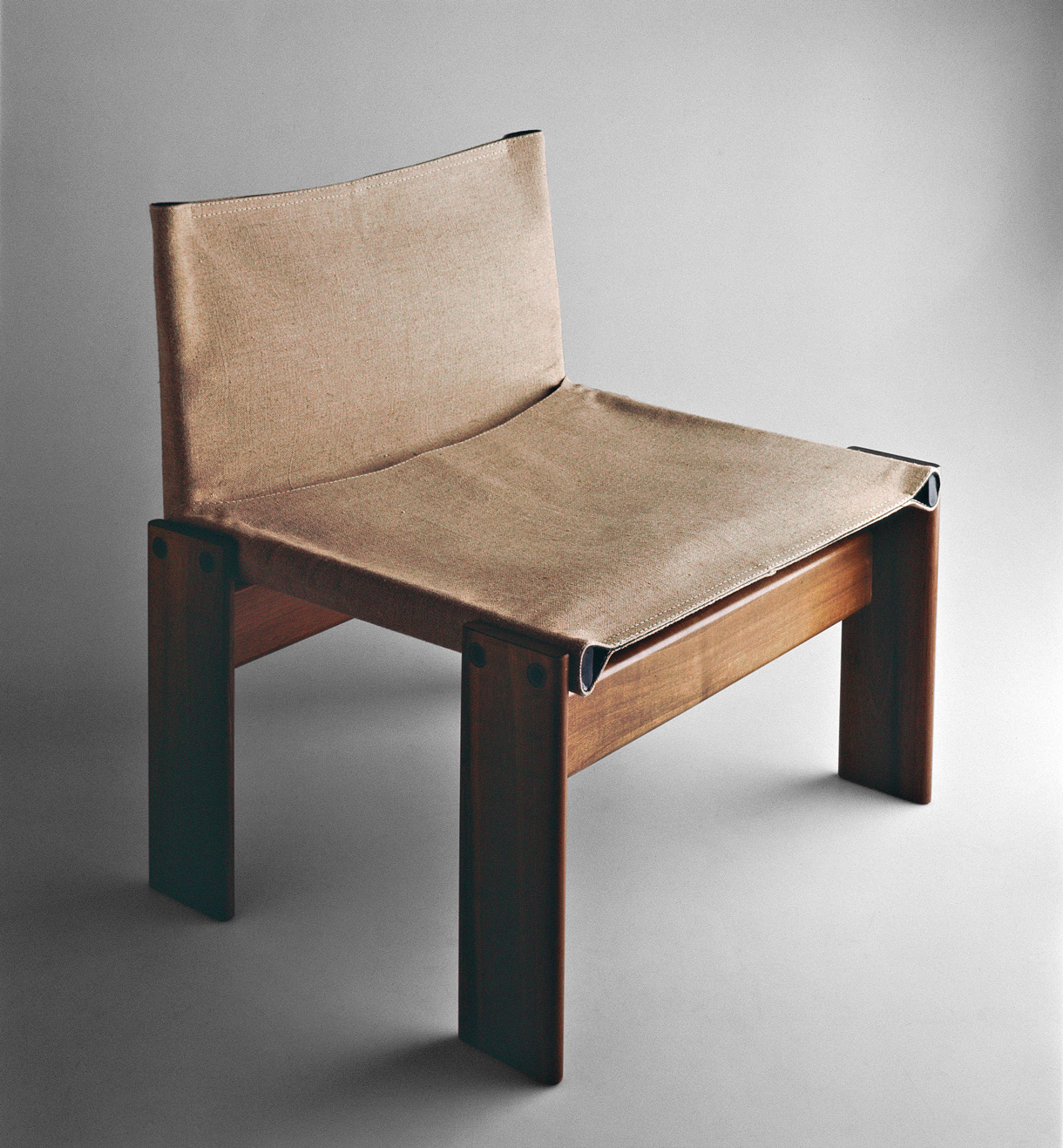

Monk (1973-74), Afra and Tobia Scarpa, Molteni&C

Monk (1973-74), Afra and Tobia Scarpa, Molteni&C

While most high street brands still lag behind, fresh inspiration is coming from a rising generation of emerging designers showcasing a future where fashion and sustainability go hand in hand. US designer Gannon McHugh, for instance, turned his focus to the afterlife of a product when creating his DFD (Designed for Deconstruction) trainer during his studies at the University of Cincinnati. McHugh’s research discovered that a staggering 300 million pairs of shoes are discarded annually.

One of the major contributing factors is the way that materials are glued together within conventional footwear design, making it complicated for recycling. In answer to this, McHugh’s trainer is held together with a metal fastening that can easily be removed, thereby separating each component for disposal. Made up of five different layers, the DFD trainer incorporates materials that can be remade into upholstery filling chips, wool that can be shredded and re-spun into new fibres, and recycled plastic laces and webbing. With the shoe's aesthetic analogous to those retailed by sportswear brands across the globe, McHugh’s trainer proves that design does not need to be compromised when adopting a circular mindset.

“We, as designers, have the ability to change the way consumers view their products. If one component gets damaged it is easy to replace or repair them without replacing the whole shoe.”

Within the construction industry, architects are now looking at modular systems to allow for disassembly and deconstruction. UK-based architecture practice Studio Bark has collaborated with engineering firm Structure Workshop to create U-Build, a modular construction kit. While U-Build lets users erect the structure themselves and personally customise the design, its superseding benefit is its adaptive functionality. When requirements change, the system can be taken apart, reconfigured, or moved to a different location. Applying this mentality to architectural structures is revolutionary, especially for temporary constructions.

Monk (1973-74), Afra and Tobia Scarpa, Molteni&C

Monk (1973-74), Afra and Tobia Scarpa, Molteni&C

At this year’s Stockholm Furniture and Light Fair, disassembly played a pivotal role in a variety of stand designs. Note Design Studio, which collaborated with a number of brands on their displays, ensured that the disposal of each structure was a governing factor when planning the initial concepts. In the case of Note’s stand for Oslo-based furniture brand Vestre, which won the fair’s Best Stand Award, each component could be repurposed once the show was over.

Flooring brand Tarkett also worked with the studio to create a temporary installation that mirrored the brand’s stance towards a closed-loop economy. Recently opening an in-house recycling facility in Waalwijk, the Netherlands, Tarkett has created its own process to ensure carpet tiles can be deconstructed and recycled into new collections.

Collaborating with Aquafil, creator of recycled nylon waste material Econyl, they launched the ReStart take-back programme, an initiative allowing customers to return used tiles to be taken apart and recycled in-house.

Looking forwards, disassembly needs to become a fundamental principle that product designers abide by. McHugh feels it could be possible.

“It is unclear how soon that will happen,” he says. “But the awareness of it is becoming increasingly prevalent. Sustainability has become a core focus and I believe the future generation of designers coming forward will continue this.”

This positive shift brings fresh optimism in the attempt to reevaluate global manufacturing. Entrepreneurs, makers and creators are building practices with inherently mindful viewpoints, giving consumers vital assurance in finding solutions that marry design- led aesthetics, superior quality, and an ethically and environmentally conscious production.

Kitchens are everyday spaces that exist to meet an immediate functional goal. When well designed, they are highly calibrated to support the convenient preparation of food.

In the centre of Milan, a short walk from the duomo, is Villa Necchi Campiglio, designed by Piero Portaluppi (1888-1967) for the Necchi Campiglio family between 1932 and 1935.

How we understand the world of design can depend on the means by which we engage with the subject.

Thanks for your registration.